SPECTROstar Nano

Absorbance plate reader with cuvette port

Cell metabolism is the sum of all chemical and biochemical reactions that take place in biology to sustain life, allowing organisms to maintain their structures, grow, proliferate, and react to environmental changes. The main function of metabolism is the conversion of nutrients into energy to run cellular processes, into basic molecules to be used as building blocks for cell growth, and the elimination of useless by-products.

In biology, the word “metabolism” also refers to the process of digestion and the absorption and transport of nutrients to and among tissues and cells. This blog post focuses mainly on metabolic processes happening in eukaryotic cells but you can read more about bacterial metabolism here.

Dr Tobias Pusterla

Dr Tobias Pusterla

Tobias Pusterla’s scientific background spans veterinary biotechnology, cancer cell biology, and the molecular mechanisms underlying inflammation‑driven tumorigenesis. After graduating in Veterinary Biotechnology at the University of Milan, Italy, he worked in mouse mutagenesis before completing a Ph.D. in Cellular and Molecular Biology through a joint program between the Open University of London, UK and the San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy. He later conducted postdoctoral research at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, Germany, focusing on tumor biology, the tumor microenvironment, and the role of chronic inflammation in cancer development. His scientific work has contributed to understanding how damage‑associated molecular signals drive immune activation, cell migration, inflammation, and tumorigenesis, helping to clarify fundamental pathways linking cellular stress responses to physiological and pathological outcomes. After more than 13 years of research experience, he joined BMG LABTECH in 2013. Here, he oversees global marketing activities, including the creation of scientific content and the coordination of application support.

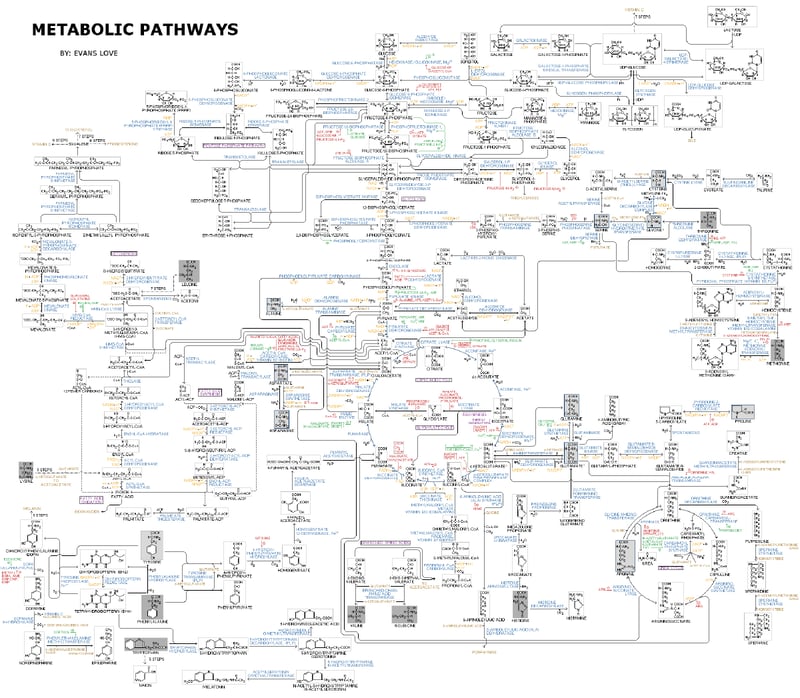

Cell metabolism encompasses different steps and sequences of molecular conversions. This coordinated series of biochemical reactions where the product of one conversion becomes the substrate for another reaction is known as metabolic pathways. In these pathways, molecules are transformed by a series of enzymes. These metabolic pathways consist of numerous chemical reactions that are essential for the transformation and regulation of cellular functions.

Basic metabolism can be simplified to pathways focusing on the use of major nutrients such as glucose, amino acids and fatty acids which are fundamental for energy production, homeostasis and growth (Fig. 1). These metabolic pathways drive various cellular processes, enabling cells to sustain life, adapt to environmental changes, and maintain overall organism health.

In biology, scientific research on cell metabolism focuses on different topics such as understanding the fundamental metabolic processes, metabolic changes and their role in diseases (including cancer cell and tumor metabolism), the development of therapies, the identification of unknown metabolic processes and metabolites, etc. However, this is complicated by the large size of metabolic networks and reactions. These networks involve the synthesis and breakdown of complex organic molecules and large molecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides, which are key products and substrates in cellular metabolism. The assembly and disassembly of complex molecules, as well as the organization of cellular components, highlight the scale and intricacy of metabolic networks. As today, more than 8,700 metabolic reactions and 16,000 metabolites are annotated.1

Metabolic reactions are interconnected and produce and recycle the components required for fundamental activities like cell growth (e.g., nucleotides, amino acids, Adenosine triphosphate - ATP) and signaling (e.g., cAMP). Enzymes allow the fine regulation of metabolic pathways to maintain a constant set of conditions in response to changes in the cell's environment, a process known as homeostasis. These interconnected reactions form a reaction pathway, where enzymes facilitate the sequential transformation of substrates into products.

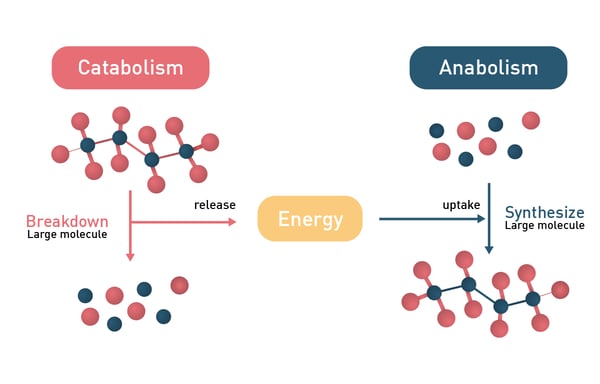

In general, metabolic reactions can be divided into catabolic and anabolic processes with the former releasing energy and the latter consuming it (fig.2). Anabolic reactions require energy input to drive the synthesis of complex molecules, while metabolic regulation also involves energy expenditure, particularly through gut hormones and neuropeptides that influence digestion and appetite.

Cellular metabolism also includes the disposal of waste and by-products. When recycling components, key metabolites act as regulatory molecules within metabolic pathways, influencing enzyme activity and pathway regulation through mechanisms like feedback inhibition.

Anabolic metabolism

Anabolic metabolismAnabolism involves the synthesis of complex molecules from simpler precursors, using energy to drive these reactions. This set of processes enables cells to polymerize simple molecules into macromolecules (e.g., nucleic acids, enzymes, etc.).

In the cell, these macromolecules are synthesized in a step-by-step process from simple precursors. The anabolic process consists of three basic stages: the production of precursor molecules (e.g., nucleotides, monosaccharides, etc.), their activation into reactive forms, and their assembly into complex molecules and polymers (e.g., DNA, proteins, polysaccharides, etc.).

These macromolecules serve as essential cellular building blocks, supporting biomass accumulation and cell proliferation. Energy, primarily in the form of ATP, is required to drive each stage of anabolism and maintain processes in the cell.2 In times of energy surplus, cells convert excess glucose into storage forms such as glycogen and fats through anabolic pathways, effectively storing energy for future use.

Organisms are categorised based on their anabolism and according to the source used by cells to build-up molecules. Autotroph organisms (e.g., plants) produce the required macromolecules from simple precursors like CO2 and H2O, whereas heterotrophs require a source of more complex substances (e.g., monosaccharides like glucose).

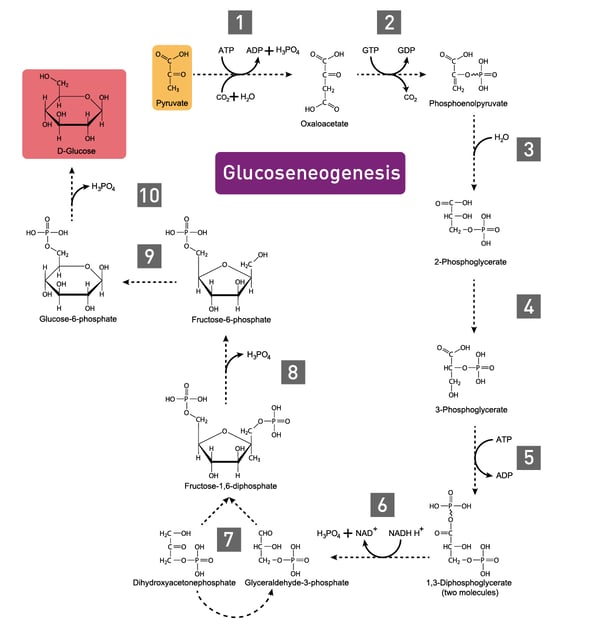

In carbohydrate anabolism, organic acids are converted into monosaccharides (e.g., glucose) and finally assembled to complex sugars (polysaccharides). These polysaccharides and proteins are examples of complex organic molecules, assembled from simpler units such as monosaccharides and amino acids. Gluconeogenesis, the generation of glucose, enzymatically converts pyruvate to glucose-6-phosphate (fig. 3).3 Glucose molecules are then stored as an energy resource in most tissues or as fat. In vertebrates, the fatty acids though cannot be converted to glucose by gluconeogenesis as these organisms do not have the necessary enzymatic machinery, as opposed to plants and bacteria.4 Alternatively, the metabolite acetyl CoA is again fed into the Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle for the production of energy.

Polysaccharides are made by the sequential addition of monosaccharides by glycosyltransferase and result in straight or branched structures. These complex sugars can then be transferred to lipids and proteins or used for metabolic or structural purposes.5

Polysaccharides are made by the sequential addition of monosaccharides by glycosyltransferase and result in straight or branched structures. These complex sugars can then be transferred to lipids and proteins or used for metabolic or structural purposes.5

Glucose is used as a substrate for glycogenesis, the synthesis of glycogen, a multibranched glucose polysaccharide. Glycogen serves as short-term energy reserve compared to fat deposits and is mainly stored in liver and muscle cells.

Proteins are made of amino acids linked by a chain of peptidic bonds. Amino acids are synthesized from intermediate products of glycolysis, the TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle), or the pentose phosphate pathway. Organisms vary in their metabolic capability to synthesize amino acids. While bacteria and plants can synthesize all twenty, mammals are limited to the eleven non-essential ones, the remaining nine essential ones must be gained from food.6

Amino acids are also used as a source of nucleotide precursors. Adenine and guanine are synthesized as nucleosides from the precursor nucleoside inosine monophosphate. Cytosine and thymine origin from glutamine and aspartate. Nucleotides are synthesized in pathways that require large amounts of energy and phosphate groups are essential components of nucleotides, playing a critical role in the structure of DNA and RNA as well as in cellular energy transfer. Fatty acids instead are polymerized by enzymes called fatty acid synthases. These extend their acyl chains in a reaction cycle.

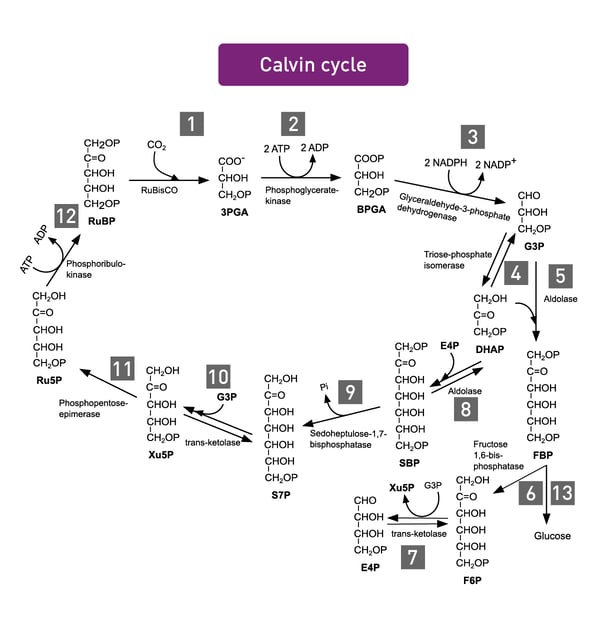

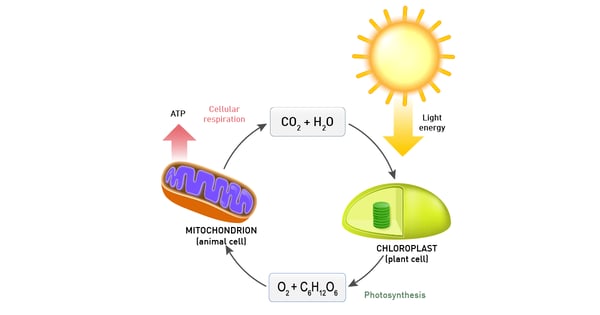

Photosynthesis encompasses all cellular metabolic pathways that enable carbon fixation and the synthesis of carbohydrates from carbon dioxide (CO2) and sunlight. This cellular process is used by plants, cyanobacteria, and algae to capture light energy and convert it into chemical energy. In the Calvin cycle, this process uses ATP and NADPH to convert CO2 to glycerate 3-phosphate and ultimately to glucose (fig.4). There are three different types of photosynthesis in plants: C3 carbon fixation, C4 carbon fixation and Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM) photosynthesis. They differ by the path that CO2 takes to the Calvin cycle.

Catabolic metabolism

Catabolic metabolismCatabolic pathways are used by cells to break down and degrade large molecules and complex molecules, such as proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides. The final purpose of catabolism is to produce energy and the basic components required by anabolism. Depending on the used substrates, tge chemical reactions can be divided in carbohydrate, protein, and fat catabolism. Catabolic pathways are essential for cell survival and play a critical role in the cellular response to stress by providing energy and metabolic intermediates.

Organisms can be divided in different groups based on their catabolism which determines whether specific substances are used as nutrients or are rather toxic. Organotrophs degrade organic molecules, lithotrophs use inorganic components, phototrophs convert sunlight to chemical energy, whereas chemotrophs depend on redox reactions. Catabolic reactions are typically exothermic.

In eukaryotes, proteins, carbohydrates and lipids are the main fuel molecules. Besides the digestion taking place in the alimentary tract of multicellular organisms, catabolic reactions include three main steps. Outside of the cell, complex organic molecules (e.g., polysaccharides, lipids and proteins) are broken down into smaller components without any energy output. These are taken up and converted by cells to smaller molecules (usually acetyl coenzyme A; acetyl-CoA) through processes involving enzyme complexes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, which converts pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and links glycolysis to the citric acid cycle. This process produces energy. In the third step, acetyl-CoA is oxidized to water and CO2. This happens in the citric acid cycle and in the electron transport chain of mitochondria. This step produces a larger amount of energy while reducing NAD+ to NADH.7 During starvation, cells can synthesize glucose from other materials or send fatty acids into the citric acid cycle to generate ATP.

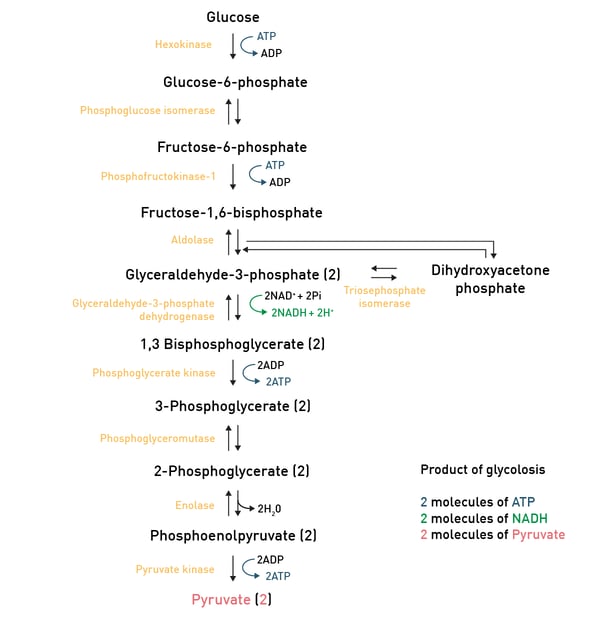

In carbohydrate catabolism, polymeric carbohydrates like glycogen are first broken down to smaller components such as monosaccharides. The glucose molecule, as the main substrate for glycolysis, is typically degraded through this reaction pathway, where it is converted to pyruvate and energy (ATP; fig. 5).

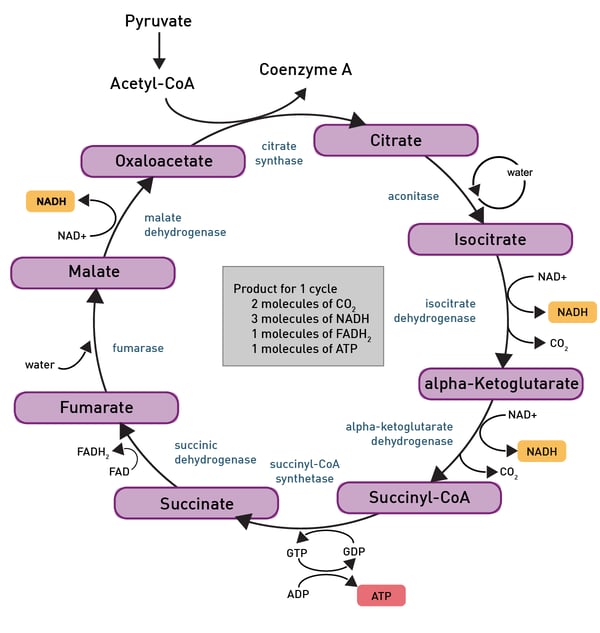

Pyruvate then is converted to acetyl-CoA through glycolysis and can then enter the TCA-cycle, another reaction pathway which produces some more ATP molecules (fig. 6).

Pyruvate then is converted to acetyl-CoA through glycolysis and can then enter the TCA-cycle, another reaction pathway which produces some more ATP molecules (fig. 6).

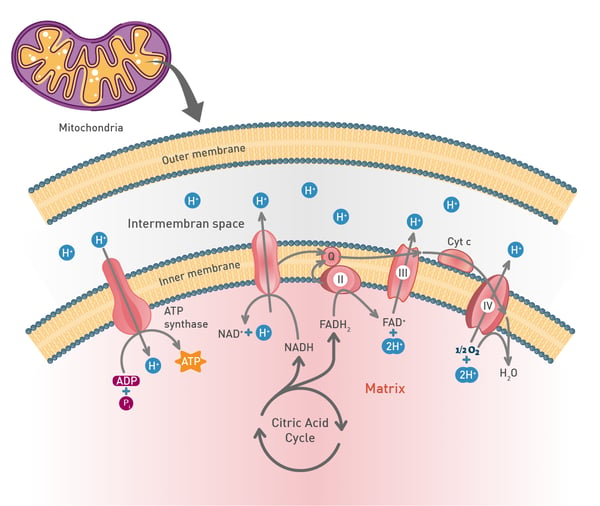

The most important product of these chemical reactions though is NADH as it is used by the electron transport chain in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes (fig.7). Oxidative phosphorylation is used here to oxidize substrates: the electrons removed from organic molecules in previously mentioned pathways are transferred to oxygen and the resulting released energy is used to produce a multiple of the amount of ATP previously made available during glycolysis.

The most important product of these chemical reactions though is NADH as it is used by the electron transport chain in the inner mitochondrial membrane of eukaryotes (fig.7). Oxidative phosphorylation is used here to oxidize substrates: the electrons removed from organic molecules in previously mentioned pathways are transferred to oxygen and the resulting released energy is used to produce a multiple of the amount of ATP previously made available during glycolysis.

In the mitochondria, a proton concentration difference across the membrane is created by pumping protons out of the organelles. This creates an electrochemical gradient that drives protons back into the mitochondrion through the enzyme ATP synthase. Through this enzyme, the flow of protons can be used to phosphorylate adenosine diphosphate to the highly energetic ATP.8

In the mitochondria, a proton concentration difference across the membrane is created by pumping protons out of the organelles. This creates an electrochemical gradient that drives protons back into the mitochondrion through the enzyme ATP synthase. Through this enzyme, the flow of protons can be used to phosphorylate adenosine diphosphate to the highly energetic ATP.8

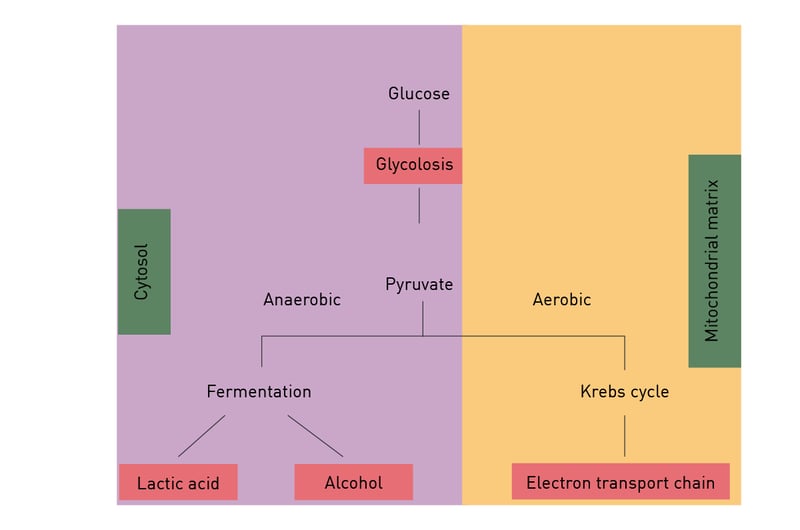

Anaerobic respiration is used when only limited amounts of oxygen are available. Under these conditions, depending on the organism lactate and/or ethanol are produced from the pyruvate generated during glycolysis (fig. 8). Though much faster than aerobic respiration, it yields a much lower amount of ATP molecules.

Fats are degraded to free fatty acids and glycerol by hydrolysis. Fatty acids are further catabolised by beta oxidation to acetyl-CoA and generate more energy than carbohydrates. Glycerol is degraded by glycolysis. Amino acids can be oxidised to urea and CO2 to produce energy.

Fats are degraded to free fatty acids and glycerol by hydrolysis. Fatty acids are further catabolised by beta oxidation to acetyl-CoA and generate more energy than carbohydrates. Glycerol is degraded by glycolysis. Amino acids can be oxidised to urea and CO2 to produce energy.

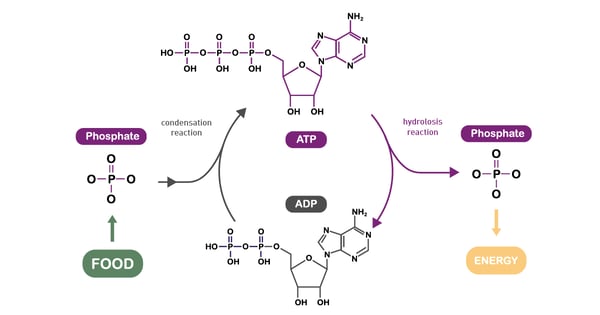

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a central co-enzyme and the main cellular energy carrier. In fact, the energy released when the chemical bonds of nutrients are broken is mainly captured in ATP molecules (fig. 9). Although in cells there are only small amounts of ATP, it is continuously degraded and regenerated. Actually, an adult human body consumes its own weight in ATP in a single day.8 Catabolism generates ATP while anabolism consumes it.

ATP can be synthesised in two ways. The first is oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria. The predominant pathway of ATP synthesis in most eukaryotic cells, it involves ATP synthesis from ADP and phosphate. In the second process, ATP is produced via the transfer of high-energy phosphoryl groups from energy molecules to ADP. This process takes place during glycolysis and during the TCA cycle. Per unit of glucose, glycolysis is an inefficient means of generating ATP compared to the amount obtained by mitochondrial respiration.

Plants and different bacteria take their energy from sunlight. Typically, the conversion of solar light into energy is similar to oxidative phosphorylation as energy is stored as a proton concentration gradient that drives ATP production.9 The main difference is that the electrons needed come from light-gathering proteins (fig. 10).

Lipid metabolism is a fundamental component of cellular metabolism, encompassing the intricate chemical reactions by which cells synthesize and break down lipids to meet their energy and structural needs. Fatty acids, as key building blocks of complex lipids, are central to these metabolic pathways. During periods when glucose availability is limited, cells rely on them as a primary source of energy. Through the process of beta-oxidation, fatty acids are transported into the mitochondria, where they are systematically broken down into acetyl-CoA units. These acetyl-CoA molecules then feed into the citric acid cycle, driving the production of ATP and supporting cellular energy metabolism.

Conversely, when energy is abundant, cells can convert excess acetyl-CoA into fat through lipogenesis, storing energy in the form of triglycerides for future use. This dynamic balance between synthesis and degradation is tightly regulated and is crucial for maintaining normal metabolism and cellular function. Disruptions in lipid metabolism can lead to metabolic stress, impacting not only energy production but also the integrity of cellular membranes and signaling pathways. Understanding how metabolic pathways involving fatty acids integrate with other cellular metabolic pathways provides valuable insight into the metabolic characteristics of both normal and disease states, such as cancer, where lipid metabolism is often reprogrammed to support rapid cell growth and survival.

Metabolic by-products are waste substances that cannot be further processed by the organism and are partly toxic in high quantities. Therefore, they have to be excreted from the cells, tissues and finally organism to maintain cellular health and homeostasis. The most common cellular metabolism waste products include water, CO2 and nitrogen compounds. Besides CO2, which is excreted by the lungs, in complex organisms metabolic waste is typically excreted through the kidneys as water solute.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are partially reduced metabolites of oxygen and by-products of aerobic metabolism, cellular respiration and photosynthesis in mitochondria, peroxisomes and chloroplasts. They are strongly oxidizing and, at high concentrations, are deleterious to cells damaging DNA, proteins and lipids, and eventually leading to cell death. However, at low concentrations, they exert signaling and gene expression functions. For instance, hydrogen peroxide also acts as a second messenger in different signaling pathways.

To maintain reactive oxygen species at low levels, cells exploit different antioxidant systems. For instance, NADPH generated during glucose metabolism is an important redox cofactor for the antioxidant enzyme ‘glutathione reductase’. This shows how cell metabolism is strongly interlinked to the redox state.

Metabolic perturbations and metabolic reprogramming are associated with common human diseases. In fact, metabolism should not be considered as a self-regulating entity that is independent of other biological pathways. On the contrary, cell metabolism affects or is affected by a multitude of processes and their regulation plays a crucial role in disease development and progression. Proper regulation of cellular metabolism is essential for cell survival, as it ensures that cells can adapt to changing environments and maintain viability under stress or disease conditions. The cellular response to metabolic stress involves activation of pathways that help maintain homeostasis, such as DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and metabolic regulation.

This is even more evident considering the fact that, during the course of evolution, fundamental energy metabolism pathways have not been modified and still are conserved throughout vastly different species. For instance, intermediates of the TCA cycle are present in all known organisms from unicellular bacteria to complex and large multicellular organisms like elephants.10 Metabolism is evidently perturbed in different diseases like cancer, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. In cancer and other diseases, metabolic changes can lead to epigenetic modifications, such as those caused by oncometabolites that disrupt DNA methylation and histone demethylation, contributing to tumorigenesis.

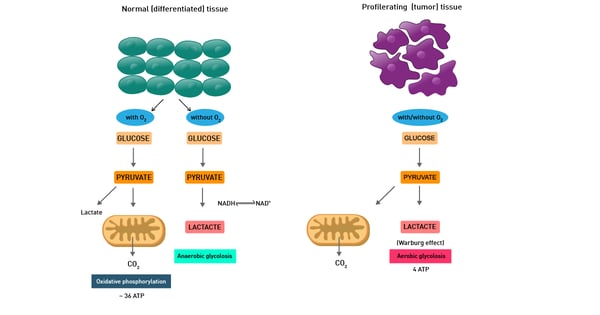

A modified cell metabolism supports the malignant transformation in cancer, as well as the growth and preservation of tumors. It is therefore considered a hallmark of cancer.11 Cancer cells typically outrun surrounding cells for nutrients (e.g., glucose). Oncogenic mutations and tumor-specific signaling pathways can increase glucose uptake in cancer cells, supporting anabolic pathways and metabolism reprogramming essential for tumor growth and progression. A widespread hypothesis is that aggressive rapid cancer cell growth and its associated increased bioenergetic demands force cancer cells to a reprogramming of their cellular metabolism pathways.12

This is mainly described as the Warburg effect from German scientist Otto Warburg, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1931. Warburg´s fundamental observation was that cancer cell metabolism typically produces energy through the less efficient glycolysis pathway instead of the most efficient TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation pathways, as normal cells do (fig. 11).

In fact, even in the presence of oxygen, cancer cells rely mainly on anaerobic lactic acid fermentation taking place in the cytosol. The detailed mechanism of cancer cell metabolism and of the Warburg effect and its therapeutic implications are still unclear. In addition, cancer cells also typically display enhanced reactive oxygen species levels.

The aberrant cancer metabolism can be exploited in diagnosis and therapy. In diagnostics, the increased glucose metabolism of cancer cells is used in positron emission tomography (PET) scans. In anti-tumor therapy development, this effect is a main focus of drug discovery and therapeutic intervention, aiming to exploit metabolic differences between tumor and normal cells. However, therapeutic strategies targeting tumor metabolism may be complicated by the fact that normal proliferating cells share similar metabolic requirements and adaptations, posing challenges to effective intervention.

In biology, metabolic readouts can be used as key molecular indicators of a healthy cellular metabolism or as predictors of disease (e.g., cancer, diabetes, etc.). These readouts also play a role in drug discovery. Here, the drug-mediated “adjustment” of metabolic pathways (metabolic reprogramming) can be used to restore a healthy phenotype to enhance cell performance, or to specifically target and kill cancer.

In biology and life science applications, basic molecular analysis of cell metabolism typically focusses on the two main pathways: glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration. These play a critical role in different molecular processes and can be used as indicators of cell health and disease, as well as of cell proliferation, death and homeostasis.

Modern microplate readers play an important role as they enable the analysis of different metabolic parameters in higher throughput and in an automated manner.

In addition, the dedicated cell-culture features of BMG LABTECH plate readers enable the monitoring of metabolic activity in real-time in live cells and with more physiological conditions, providing important details about cell homeostasis, mitochondrial function, and substrate and energy consumption.

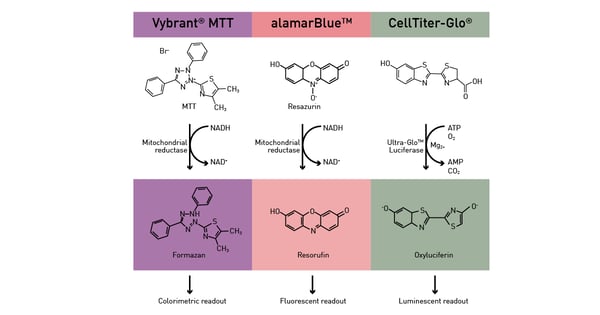

Metabolic microplate-based assays can be divided in two categories: the ones that exploit metabolic activity as an indirect readout and the ones that directly target specific pathways. For the former, enzymatic pathways as well as ATP presence are exploited as readout to analyse different functions in cells. An active metabolism is a sign of viable cells and can be hence exploited by viability assays (fig.12) as described in the app notes Viability assays: a comparison of luminescence-, fluorescence-, and absorbance-based assays to determine viable cell counts and The new Atmospheric Control Unit (ACU) for the CLARIOstar provides versatility in long-term cell-based assays. In addition, ATP is used as fuel by many luciferase-based assays.

Direct metabolic readouts focus mainly on glucose consumption, mitochondrial function, glycolytic activity and generation of by-products (radical oxygen species). Glucose presence in the cell culture medium and its consumption by cells over time can also be assessed by luminescence, as shown in the app note Glucose assay and lactate assay allow to monitor cellular glucose metabolism precisely.

Direct metabolic readouts focus mainly on glucose consumption, mitochondrial function, glycolytic activity and generation of by-products (radical oxygen species). Glucose presence in the cell culture medium and its consumption by cells over time can also be assessed by luminescence, as shown in the app note Glucose assay and lactate assay allow to monitor cellular glucose metabolism precisely.

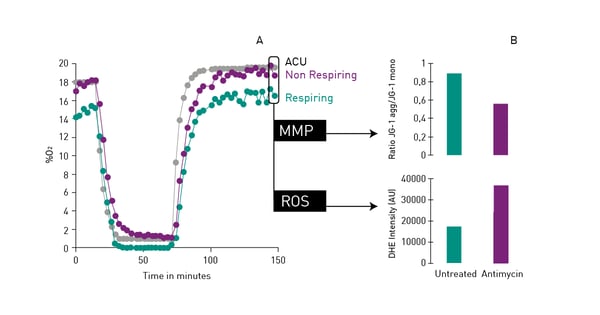

Mitochondrial function is commonly evaluated through the analysis of oxygen consumption. In the app note Real-time monitoring of intracellular oxygen using MitoXpress-Intra, the MitoXpress Intra assay is used to measure oxygen consumption with an oxygen-sensitive fluorescent probe. As cells respire, the depletion of oxygen within a cell monolayer is analysed kinetically in real-time on a CLARIOstar® Plus microplate reader with Atmospheric Control Unit (ACU). The ability of the CLARIOstar Plus with ACU to run gas ramps also enables studies in hypoxic environments as shown in the app note The CLARIOstar with ACU exposes cells to ischemia-reperfusion conditions and monitors their oxygenation (fig. 13). These assays can also be used for safety assessments as well screenings for drug-induced metabolic side effects and mitochondrial dysfunction. This can considerably influence organ toxicity for instance in the heart, liver and kidney.  NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ are cofactors used by many enzymes in metabolism and for different mitochondrial functions. The reduction of NAD+ to NADH and NADP+ to NADPH can be easily monitored in absorbance as their oxidized forms do not absorb light at 340 nm (fig. 14).

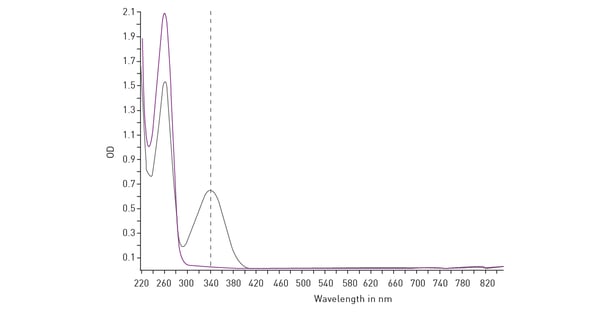

NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ are cofactors used by many enzymes in metabolism and for different mitochondrial functions. The reduction of NAD+ to NADH and NADP+ to NADPH can be easily monitored in absorbance as their oxidized forms do not absorb light at 340 nm (fig. 14). Glycolytic activity under anaerobic conditions is typically evaluated by means of the analysis of extracellular acidification. The conversion of pyruvate to lactate and its secretion in the extracellular environment thereby leads to the extracellular acidification of the cell culture medium. In cancer cells, lactate presence can be used as a marker of disease.

Glycolytic activity under anaerobic conditions is typically evaluated by means of the analysis of extracellular acidification. The conversion of pyruvate to lactate and its secretion in the extracellular environment thereby leads to the extracellular acidification of the cell culture medium. In cancer cells, lactate presence can be used as a marker of disease.

Lactate is quantified by time-resolved fluorescence in the app note Assessment of extracellular acidification using a fluorescence-based assay. Another luminescence-based method is shown in the app note Glucose assay and lactate assay allow to monitor cellular glucose metabolism precisely.

Cellular redox changes can be monitored in different ways. One approach is to use genetically encoded biosensors based on redox-sensitive GFP (roGFP). Further, the following blog post discusses ROS detection in general.

Cell metabolism is a highly coordinated network of biochemical reactions that enables cells to generate energy, build essential biomolecules, and maintain homeostasis. From anabolic synthesis to catabolic breakdown, these pathways ensure that cells can adapt to changing environmental and energetic demands. Disruptions are central to many diseases, including cancer, where metabolic reprogramming becomes a defining feature of malignant progression. As metabolic pathways continue to reveal their complexity, modern analytical tools—such as advanced microplate‑based assays—provide essential insights into cellular function, metabolic health, and therapeutic responses. Understanding these interconnected processes not only deepens our knowledge of fundamental biology but also drives innovation in biomedical research and drug discovery.

Absorbance plate reader with cuvette port

Powerful and most sensitive HTS plate reader

Most flexible Plate Reader for Assay Development

Upgradeable single and multi-mode microplate reader series

Flexible microplate reader with simplified workflows

Learn about applications for bacterial metabolism on a microplate reader.

Mitochondrial toxicity can have devastating effects on the cell and life. Find out how microplate readers can be used to assess mitochondrial health and how this impacts disease and drug discovery.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) may have physiological as well as pathological effects. Here we explain what ROS are and how they can be measured on microplate readers.

Redox processes play an important role in cell homeostasis. Read here, how to monitor cellular redox changes with roGFP using the most sensitive, high-performance plate readers from BMG LABTECH.

The pH-Xtra assay is a TRF-based assay to assess extracellular acidification as a measure of glycolytic activity. Read more about the assay and its performance here.